And yet Rwanda knows how to love Congo

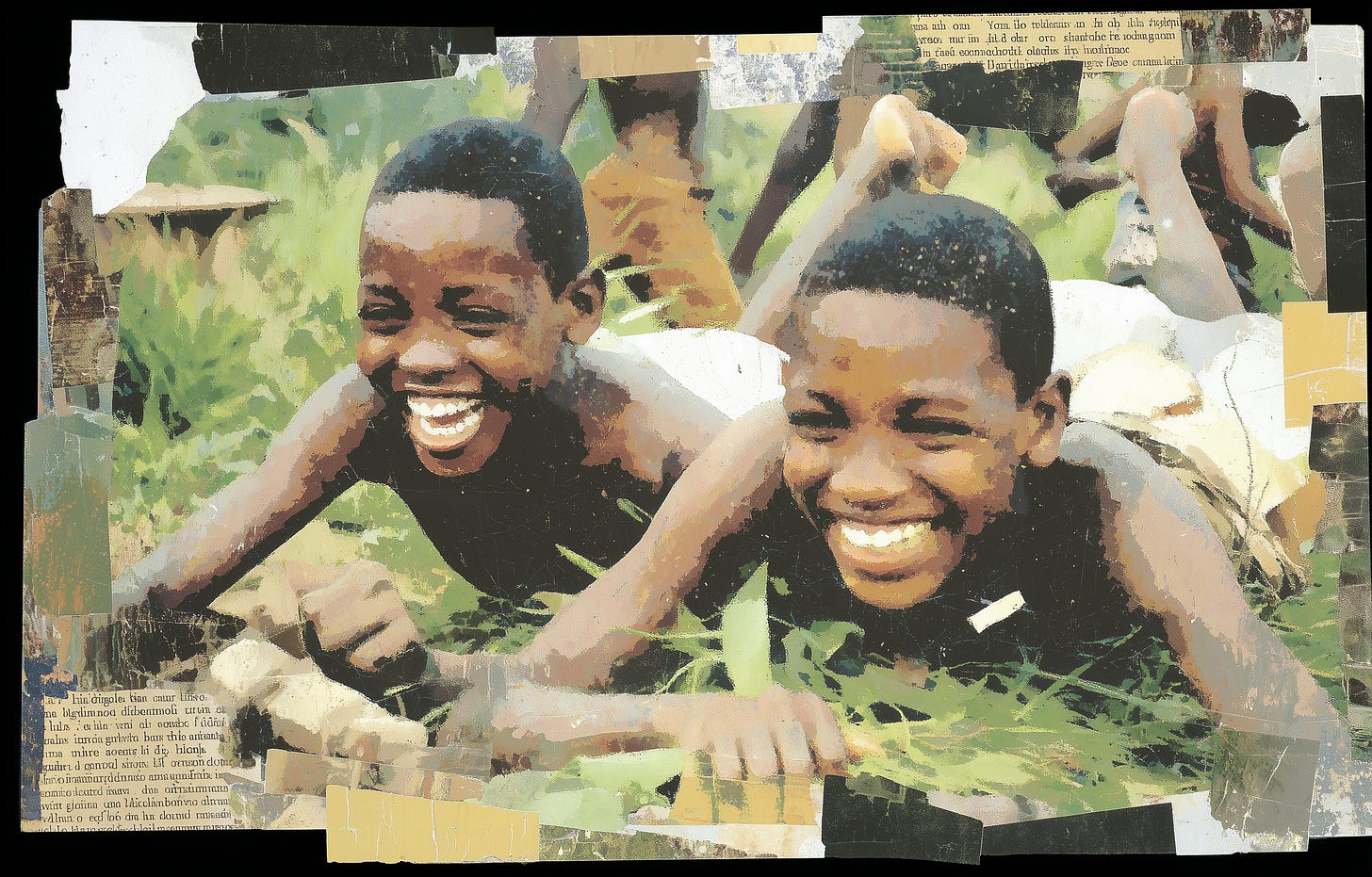

The Saint-Gilbert school in Biruma was full of joyful kids, but learned adults decided to halt the games and the smiles.

I never understood the appeal of walking every morning amidst the greenery of trees, after the dawn's dew, only to be confined between four walls where one is deprived of the joy of the wind and the beauty of games.

Each night is weighed down by the hope of the day that follows. Our hopes were subtle, unconscious, and simple. We hoped that the morning would not be too long and that we would quickly get rid of our books. Above all, we hoped to catch one or two birds, run and laugh together. We hoped to prolong these moments as much as possible before being forced to go back. Before adding to the slumbering sun with new hopes. Subtle. Unconscious. Ours.

At night, I thought about the jokes I would tell Germain. I thought about the questions I should ask Isaac. I never understood why there were two "a’s" in his name. I wondered what he did with the second. Perhaps, I already thought, his parents had a plan for that second letter.

We knew our parents had plans. We, as little children, saw in our parents' eyes greater, more conscious, and distant expectations than our own. We did not understand all of them, but we knew.

In the morning, I went to school after eating. Between the greenery of trees, the birds' singing, and the wind's breath, there was me. Me and my hope that the morning would not last, that the books would pass quickly. There was also me and my consolation in my mind; the presence of Marie.

I have never seen a girl with teeth as white as hers. I had always been impressed by her smile, the dimples on her cheeks, and the purity of her teeth. Sometimes, I looked at her and thought of the birds' singing in the morning. Her smile was as light and sweet as that. During the breaks, I called her name very loudly, then hid to see her turn around. I liked that.

According to reports, her parents were from Butare, Rwanda. Her late father had taught there. Her father and mother died together in an accident. She lived in our village with her mother's half-sister.

I am from here, my father was born in this village, but my mother, like Marie, was born on the other side of the border. In Rwanda. I wanted to be like my father. On Saturdays, my father recited poetry to Yona, my mother, and here I am.

I also wanted to recite love poems to Marie and marry her. To marry a Rwandan and have children.

The roses are red/The trees are green/My perfume is pleasant/And so are you. / Bella's flowers reach/Up to the serene skies. / The voice is sweet/And so are your eyes. / Unity/Work and love/Are as beautiful/As together our union...

That morning, I had not thought of poetry or Rwanda. Germain, Isaac, and I had to check if the traps we had set the day before were successful.

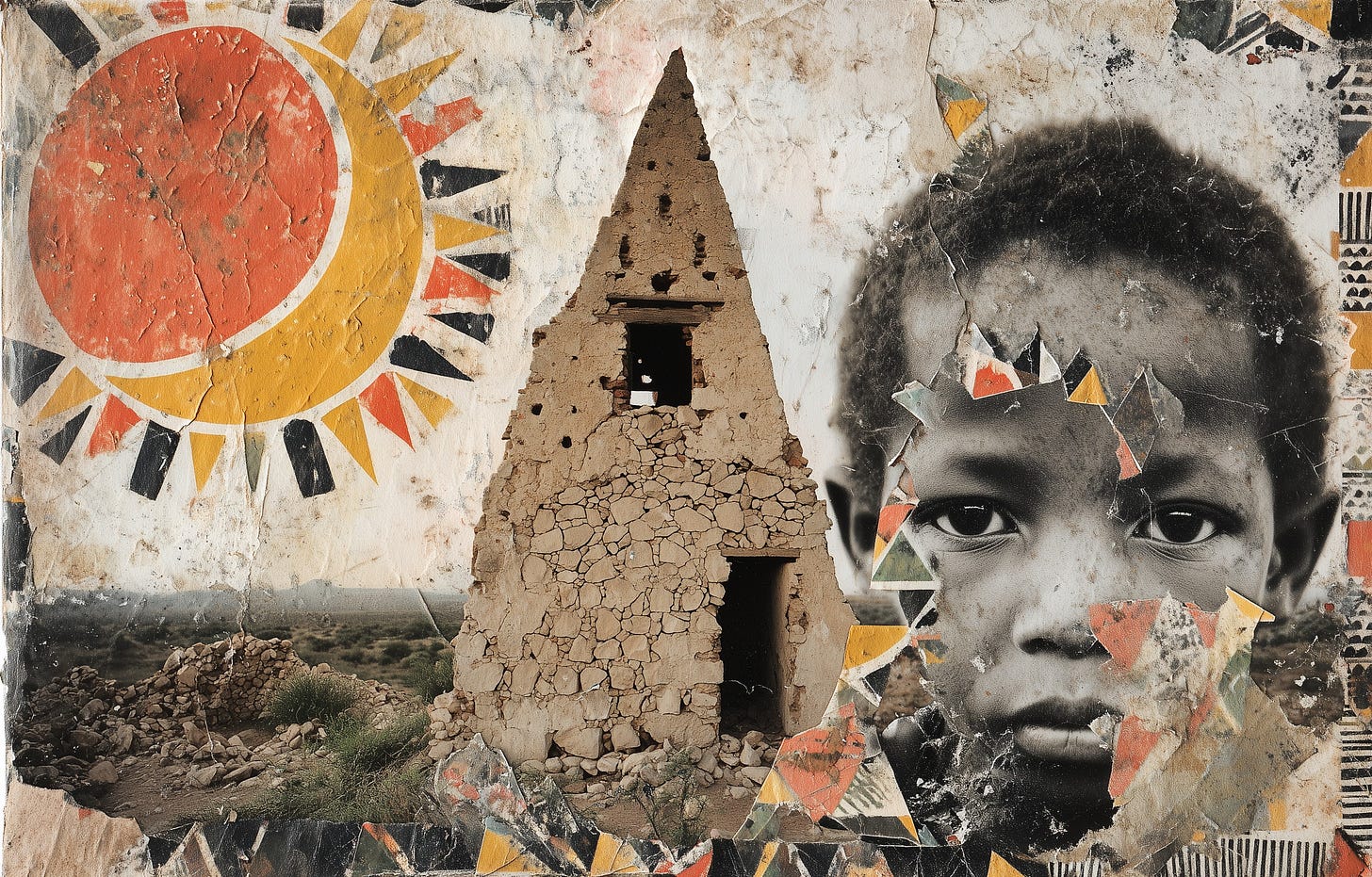

Suddenly, there was a loud noise. Then, I heard nothing. I became deaf. The loud noise deafened me, and a great dust rose.

When the dust cleared, there was a hole in the roof. Germain and Isaac were no longer there. There was only blood and pieces of human beings. I was on the ground, unable to walk.

The Saint-Gilbert school in Biruma is in mourning. Papa Joseph mourns Germain. Mama Sifa mourns Isaac. My two comrades sleep with banana tree roots. Underground. Fear makes the village run at the slightest noise. The authorities spoke of a bomb and the M23. People spoke of Rwanda hating the Congolese. All Rwandans. All Congolese. Yet, my father, Papa Promedi, has always loved my mother, Mama Yona.

I have never understood what was good about walking every morning among the green of the trees, after the dew of dawn, to go and lock oneself up between four walls where one is deprived of the joy in the wind and the beauty of games. And yet Rwanda knows how to love Congo.